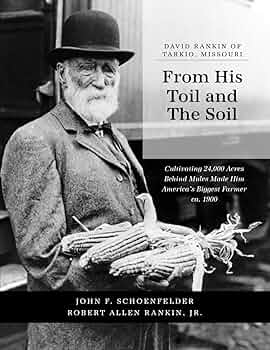

America’s biggest farmer

By Mark Lane

Submitted to Corner Post

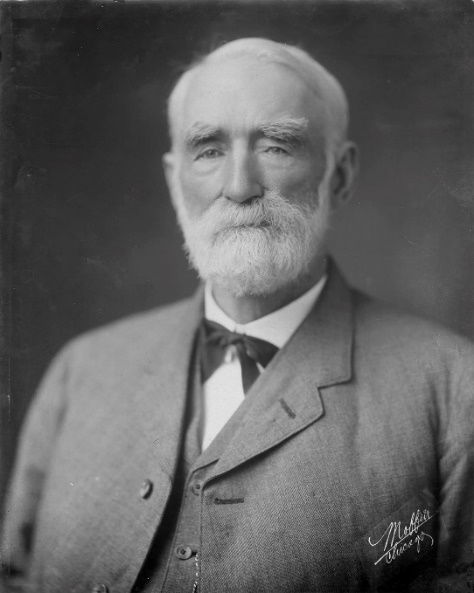

The headline of the (Ft. Collins Colorado) Weekly Courier read: WORLD’S RICHEST FARMER DIES IN TARKIO, Missouri. That article described the deceased as “an example of the rise of a poor boy to wealth and usefulness through the exercise of frugality and by taking advantage of opportunity.” In 1910 the Saturday Evening Post lauded Henry Wallace as a wise master at telling farmers how their work should be done and contrasted that by stating this gentleman from Tarkio not only tells what should be done, but he does it “on a scale that would stagger any man who is not calloused to American farm figures.” And six years before his death, an article in the Los Angeles Herald likened the Tarkio man to John D. Rockefeller for his philanthropy. (Note: Henry Wallace was featured in an article in the Jan. 23 issue of the Corner Post.)

It’s true that David Rankin started with little in the way of assets. (He went barefoot each summer until he was 28!) But he had a strong work ethic and a keen sense of turning opportunities into advancements. When his father gave him a young colt, he sold it and bought calves. After the calves grew and were fattened, he sold them and invested in more farm enterprises. Before long, he bought an 80-acre farm on credit, and within four years the loan was entirely paid off. It was a routine he repeated often, on an increasingly advanced scale.

Expanding on his early project of feeding corn to fatten calves for market, Rankin created a “feed lot” on the open range of the new state of Nebraska, a novel concept at the time. He later purchased large tracts of open land in northwest Missouri to grow crops (primarily corn) and to raise cattle and hogs — which were fattened with his corn. Ever searching for ways to do work more efficiently, Rankin innovated new equipment and new concepts to complete jobs faster and to lower production costs. In 1853, using two single-row cultivators (the standard of the time) and the front wheels of a farm wagon, he fashioned a cultivator that worked two rows at once.

At the time of his death in 1910, Rankin had over 24,000 productive acres in cultivation, with about 1000 acres more in pasture, feedlots, storage and shelters. He was also marketing around 12,000 head of cattle and 55,000 hogs annually. Power for the planting, harvesting and other work on his eleven farms was provided by more than 600 mules.

Organization was an integral part of his strategy Each foreman was responsible for the men, machinery, crops and stock on the farm to which he was assigned. Every morning by 7am, Rankin would have spoken to his eleven foremen, with each expected to provide a summary of the current situation under his supervision. Similarly, each could expect to be quizzed about details, and might even expect Mr. Rankin to ride out to the fields on any given day.

More than simply improving his own farms, Rankin endeavored to help others, too. In 1902, he established Midland Manufacturing Company and contracted with blacksmith Silas Bailor to perfect the two-row cultivator that had been used on Rankin farms for almost 50 years. (Interestingly, Bailor patented a version he built in 1892, something David Rankin had not done when he created his.) Midland Manufacturing also produced manure spreaders, hay stackers, windmills, pumps, tanks, and other equipment using assembly line practices, which lowered the cost for farmers.

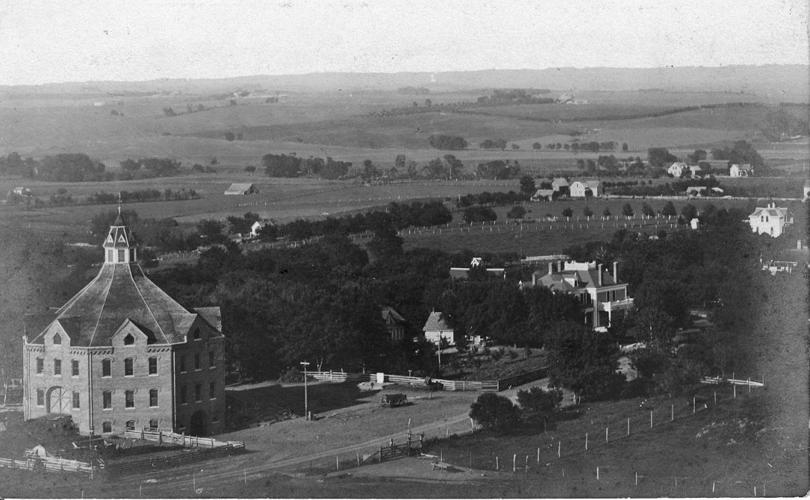

David only attended primitive schools, and only for a few years. After age 10, he worked full-time. But he valued education greatly. He endeavored throughout his life to learn useful information, especially as related to agriculture and business principles, and to apply them consistently. As his wealth grew, he made education available to others who might not have been able to attend school otherwise. He also co-founded Tarkio College in 1883. Among the alumni of that liberal arts institution are Wallace Carothers (creator of nylon and neoprene) and Marco Rubio (current U.S. Secretary of State).

To understand his early years, we must recall that Indiana and Illinois were frontiers of the nation, where there were essentially no fences to keep animals in or out. There were very few bridges for crossing rivers. Making a trip to town could take one to three days, so people learned to be chiefly self-sufficient. From a very early age David was expected to do chores. Fetching wood and tending livestock grew to include working at the little saw mill his daddy built and operated, and using a wooden plow to break virgin prairie ground. It was hard work, but David always was a “hands on” man. Even after becoming wealthy, he actively managed farming operations personally, until shortly before his death.

While certain investments in the community of Tarkio and the surrounding area benefited his business interests, many of these improved the lives of area residents, as well. Examples include a bank, an electric power company, a phone company, a cold storage facility, a kiln and an auditorium.

Imagine the contrast between the conditions of David’s early years and those of his later years. Having driven cattle to the small stockyards Chicago on foot, he later sent many railcar loads of livestock there, where the pens had grown to cover an entire square mile! His first plow was a wooden mould-board pulled by a bull (because he couldn’t afford an ox team, and steel plows hadn’t been invented); he later had hundreds of teams of mules pulling efficient, multi-row implements over thousands of acres he owned. And the boy who couldn‘t afford to attend a primitive school made high-quality education available to many thousands of students.