Burnside’s blunders cost the lives of many Union soldiers

ST. JOSEPH, Mo. (News-Press NOW) — Generally speaking, Abraham Lincoln had a big problem during the Civil War ... many of his top generals didn’t get along. Between some of them it was so contemptuous they sabotaged each other's strategies and actions, costing soldiers lives.

Fact is, to become a general you had to be ultra-confident and self absorbed, with a large dose of arrogance and defiance even after a decision had gone terribly wrong. These type-A individuals were very competitive with one another, to a fault.

Four days after the questionable Union victory at the Battle of Antietam -- a blood bath -- Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all the slaves in the “rebellious states.”

He did this not only because it was the right thing to finally do, but politically it was calculating. He put the issue of slavery at the center of national debate, not just the question of whether territories becoming new states could expand the institution.

Lincoln needed to keep the Union’s fragile momentum moving forward after Antietam, many northern Democrats not only tolerated slavery, they were in favor of a negotiated peace with the Confederacy. Lincoln would have none of it!

After failing to pursue Gen. Robert E. Lee’s wounded army into Virginia following the Battle of Sharpsburg/Antietam, Lincoln was furious. He fired Commanding Gen. George McClellan and searched the general’s bench for the right leader.

West Point graduate Gen. Ambrose Burnside was the next man up.

During the Civil War, being a Union officer was considered prestigious. The higher the rank, the more distinguished you were in the eyes of society.

Politically appointed colonels and generals plagued both sides throughout the war. The more well connected they were, the higher rank they received. Union Generals Benjamin Butler, Dan Sickles and Lew Wallace, among others, had important commands during major battles without formal military training.

Alcoholism, incompetence and cronyism were pervasive on both sides. During the war there were approximately 400 Southern Generals and more than 500 for the Union.

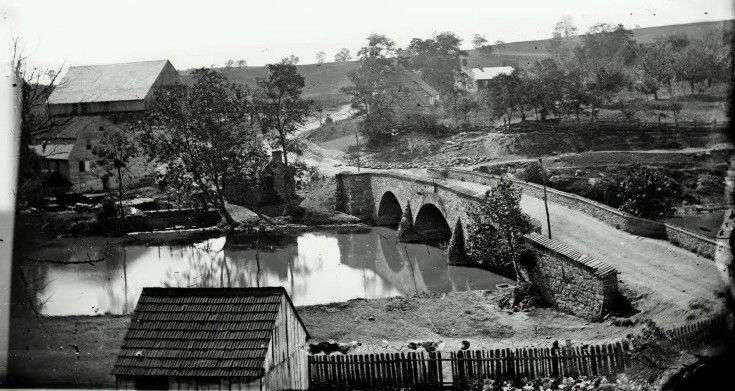

At least Burnside was well trained, but that didn’t mean he was smart. At the Battle of Antietam, Burnside commanded the 13,000-man IX Corps ordered to take the strategic bridge over Antietam Creek, a bridge that bears his name today.

The general was late to the attack, failing to coordinate with other assaults on the battlefield. His men were held off by 500 Georgians for roughly four hours, giving southern Gen. A P Hill -- wearing his trademark red vest -- time to march his light Rebel brigades 12 miles from Harpers Ferry, Virginia, into Maryland to join the fight.

Hill’s troops surprised Burnside, blasting the general's open flank and forcing a Union retreat, ending the deadliest day of the Civil War.

Even so, on Nov. 7, 1862, President Lincoln made Gen. Ambrose Burnside the overall commander of the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac. Aggressively, Burnside decided he would not make McClellan’s mistakes and strategically planned bold moves to take Richmond, the Confederate Capital, and end the war.

By this time, Ambrose Burnside would have slid quietly into anonymity were it not for his facial hair. Sideburns or lamb chops were originally called burnsides because of the bird's nest-like growth the Commander carried on either side of his face, from nose to each ear.

He started a trend to be remembered. I wonder who had the first mullet?

Fredericksburg, Virginia, was halfway between Washington D.C. and Richmond. If the Army of the Potomac could move quick enough and take the lightly-defended city, it would put itself in a good position to drive on the Rebel capital, causing Lee to attack on Burnside’s chosen terrain. It was a daring plan that Lincoln supported.

Fredericksburg lies on the southern banks of the Rappahannock River that had to be crossed. Lee had destroyed all bridges over the river months earlier, so Burnside needed to build something new and fast ... a pontoon bridge. It’s up for debate at this point whether his plans were subverted by subordinates or not.

First it took days to get the pontoons delivered to the Army, then unbelievably they were at the back of the 17-mile long Army of the Potomac caravan. Once brought forward, which added another two days, they lacked the mules to maneuver the pontoons into position, another day's delay.

All of this gave Lee ample time to maneuver his and Gen. James Longstreet’s Corps to meet Burnside's assault. The element of surprise was gone. Longstreet took up a position overlooking the town on Marye’s Heights.

General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson even had time to move his Corps from the Shenandoah Valley to cover Longstreet’s flank.

It’s December in 1862 and cold. Burnside's engineers began to lay the pontoons in place to try and cross the river. Rebel sharpshooters had plenty of success picking off these unarmed soldiers.

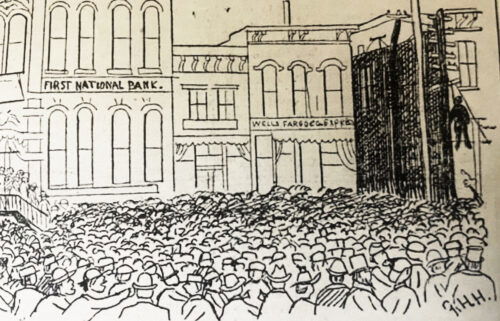

The General reverted to plan “B,” utilizing the pontoons in what is considered America’s first amphibious assault in war.

Armed Union soldiers in boats paddled the Rappahannock under fire, landing in Fredericksburg, where a short but fierce fight took place. The Rebels were overwhelmed, retreating to Marye’s Heights to join the now entrenched Jackson Corps.

Delays by the Union Army -- either caused by poor planning or sabotage -- indicates to me a pervasive destructive attitude where the Union brass actually worked against one another in several instances.

This happened on the Confederate side too. Rigid personalities, jealousy and wounded pride can be seen on the playground or battlefield.

Once Burnside took Fredericksburg, he had no idea that just outside the town were Rebel troops waiting ... perfectly positioned to deliver devastation and give the Confederacy their greatest one-sided victory of the war.

Next week ... the battle.

————————————-

Bob Ford’s History will appear in each edition of the Midweek and Weekender. You can find more of Bob’s work on his website bobfordshistory.com and videos on YouTube, TikTok and Clapper.