Architect Sou Fujimoto: Expo 2025 is ‘a precious opportunity to come together’

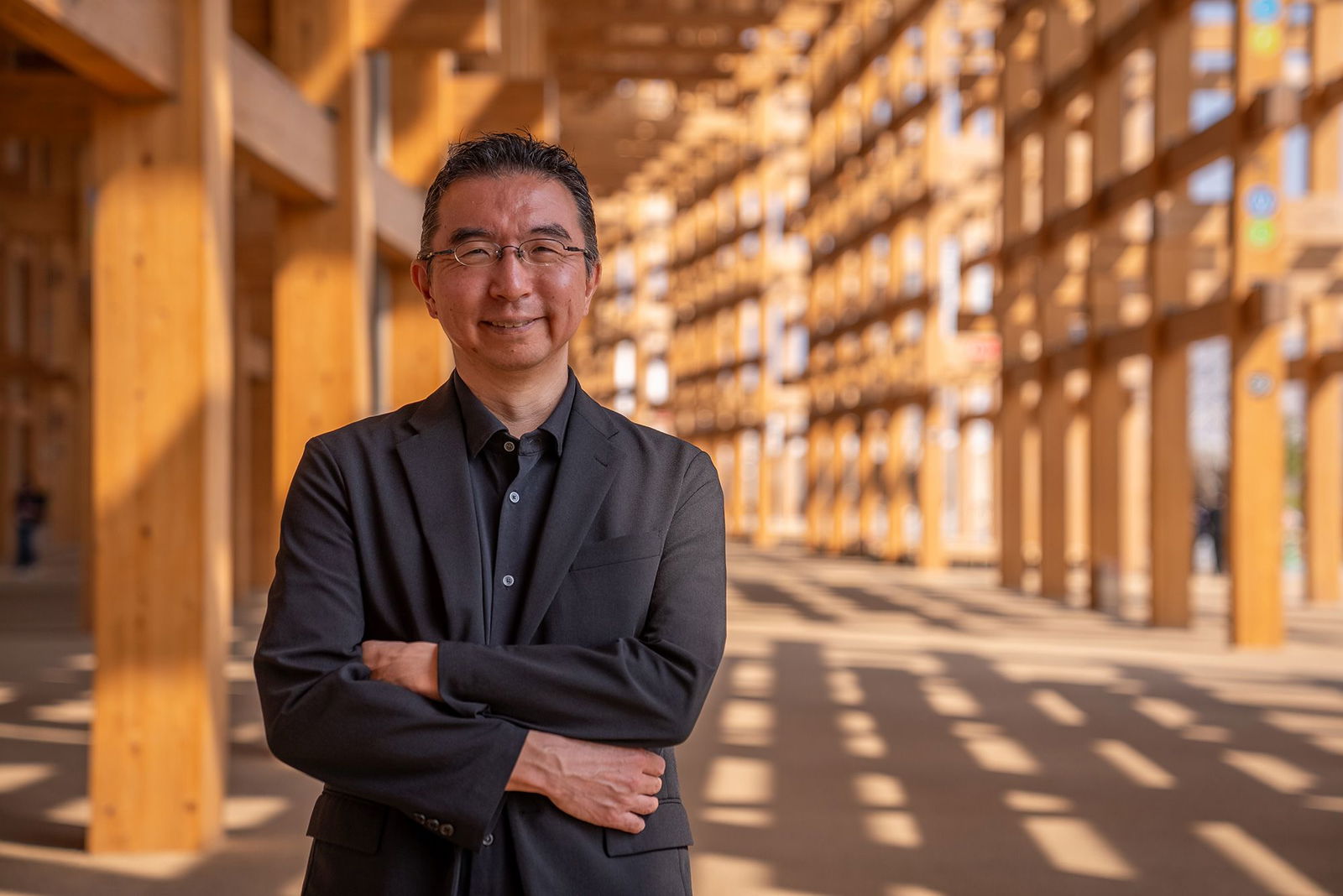

Architect Sou Fujimoto inside the Grand Ring

By Oscar Holland, CNN; Interview by Hanako Montgomery, CNN

(CNN) — Ever since the Great Exhibition opened its doors in London 174 years ago, the World’s Fair has offered nations a chance to show off the greatest inventions of the age. But Expos of recent decades have been as much about diplomacy and public relations as innovation.

It is little surprise, therefore, that the mastermind behind Expo 2025 — which commences this weekend in Osaka, Japan, just three years after the end of Dubai’s Covid-delayed Expo 2020 — doesn’t express his vision in terms of scientific or industrial progress. In an era of increasing conflict, the message is all about unity.

“The whole global situation is very unstable,” said Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, touring CNN around the site ahead of Saturday’s opening ceremony. “I believe this is a really precious opportunity to show (that) so many countries can come together in one place and think about our future together.”

Japan hopes to welcome 28 million visitors to the event between now and mid-October. Designed by Fujimoto on a 960-acre artificial island in Osaka Bay, the site will host over 150 pavilions showcasing new technology, design concepts and multimedia exhibitions under the theme “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.”

Among them are dozens of national entries, from the serenely minimalist US pavilion to the corkscrew-shaped Czech one. The main attraction, however, is the venue itself: Fujimoto’s Grand Ring, a continuous wooden structure, more than 1.2 miles in circumference, encircling much of the Expo.

Made from Japanese cedar and cypress (as well as Scottish pine), it now holds the Guinness World Record for the world’s largest wooden architectural structure. The Grand Ring is symbol of unity, too, Fujimoto said. And while it serves a functional purpose as a pedestrian route around the site, while protecting visitors from rain and sun, the structure was also designed to demonstrate the possibilities of timber as a viable alternative to carbon-intensive concrete.

“At the beginning, nobody believed it was possible,” Fujimoto said, describing the technical challenges of building with wood at such scale as “so huge.”

The use of wood in large structures, even skyscrapers, has accelerated in recent years. It’s a trend spurred by the development of advanced “mass timber” — typically made by gluing layers of compressed wood into strong columns or panels — and progressive building codes and policies promoting its use (France, for instance, now requires all new public buildings to include at least 50% wood).

Engineered timber nonetheless remains novel in much of the world. But Japan has a long and continuous history of wooden architecture. The devastating earthquakes of 1891 and 1923 exposed the shortcomings of then-popular European-style brick and stone buildings. Today, around 90% of Japan’s single-family homes are built using timber frames, which are better equipped to withstand quakes.

As such, Fujimoto’s Grand Ring looks both to the material’s future and its past. He combined modern construction methods (including steel reinforcement) with interlocking joints inspired by those traditionally used in Shinto temples and shrines. These joints required exhaustive study, with mockups made and stress-tested — sometimes to the point of destruction — to ensure their durability and seismic resistance.

Fujimoto believes his country can remain a world leader in timber construction. It is a movement he has pioneered, alongside architectural luminaries like Shigeru Ban and Toyo Ito, since his eponymous firm’s breakout project: a home in Kumamoto, completed in 2008 and named Final Wooden House, that resembles an oversized Jenga tower.

“We have such a wonderful tradition of wooden construction,” Fujimoto said. “And also, really wonderful craftsmanship from more than 1,000 years ago. So now, we can combine that kind of tradition with the latest technology to create the future of sustainable architecture.”

Fate of the Ring

The road to Expo 2025 has been, at times, bumpy for Japan. Venue construction costs have ballooned from an initial estimate of 125 billion yen ($852 million) to 235 billion yen ($1.6 billion). Public interest has meanwhile proven lukewarm, with Osaka’s governor Hirofumi Yoshimura last month admitting that the city was struggling to meet its advance ticket sale targets.

On both matters, Fujimoto struck a diplomatic note. He described the final costs as the “proper price, not too high, not too low,” while expressing hope for growing “passions and energetic interest” from the Japanese public. “The atmosphere is changing now,” he added. “So, I’m optimistic about it.”

While Fujimoto can justifiably distance himself from blame, there is another controversy to which he is more intimately tied: the fate of the Grand Ring.

Whether, or how much of, the structure will live on after the Expo is a matter of ongoing debate in Japan. It is also a bone of contention among critics who believe that dismantling the structure would undermine its message of sustainability. Regardless of his wish that nothing goes to waste, the architect realizes that the decision may hinge on the funding required for upkeep and future events.

“I, myself, (would) really like to keep it — to preserve it … because it is really wonderful, and it is like a symbol of how our society can live together with nature,” he said.

Yet, Fujimoto also notes that impermanence has always been a feature of Japanese architecture. Traditionally, the country’s wooden homes were constructed with an expected lifespan of 20 years, and many Japanese people would sooner rebuild their house than renovate it. Some of Shintoism’s most important structures, including the famous Ise Grand Shrine, have been regularly torn down and rebuilt over the centuries, posing a philosophical question — akin to the ship of Theseus paradox — of whether a building is more than the sum of its material parts.

The architect implored that, should the Grand Ring be dismantled, its wood is repurposed in other projects. Then, “even though the building is gone, the life or spirit of the materials will still be alive,” he said. In any case, the legacy he envisaged for the Expo is an intangible one: “Amazing memories and surprising experiences that inspire (visitors) to create something for the future.”

Together ‘with the cycle of nature’

One of Japan’s most celebrated living architects, Fujimoto was an obvious choice for Expo organizers. As well as practicing widely in Japan, the 53-year-old has become internationally renowned since being asked to design a temporary pavilion at London’s Serpentine Gallery, one of architecture’s most prestigious commissions, in 2013.

Other recent high-profile projects include the striking L’Arbre Blanc (“The White Tree”) residential tower in Montpellier, France, and the House of Hungarian Music, an airy arts venue whose perforated dome sits nestled among trees in a Budapest park.

Both projects are emblematic of Fujimoto’s architectural philosophy, dubbed “primitive future,” which explores the symbiotic links between people, design and the environment. It’s an outlook he has often attributed to his upbringing, amid nature, in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island.

Fittingly, greenery is woven throughout his Expo 2025 design. “(We) couldn’t live without nature,” he said, adding that the site should “show how we can be together with the cycle of nature.”

At the heart of this year’s expo lies the “Forest of Tranquility,” a congregation of around 1,500 trees, including native species like Japanese blue oak, Japanese maple and Japanese snowbell. Among them are trees replanted from Expo ’70’s Commemorative Park, some 13 miles northeast of the site, which serves as a permanent reminder of the last time Osaka hosted the World’s Fair.

Architecturally, much has changed in the intervening 55 years. Expo ‘70, held the year after the moon landing, played out under a giant “space frame” roof and exhibited a moon rock brought back to Earth by Apollo 12. The event’s lead designer, the late avant-garde architect Kenzo Tange, was known for conceptual floating cities and grand, outlandish megastructures.

Fujimoto described the event as “a glorious moment of Japan in the 20th century,” but emphasized the difference between his Grand Ring and his predecessor’s centerpiece design: “Kenzo Tange’s roof represented technology and industry… but our ring is made from wood and is a symbol of sustainability.”

Japan itself has also transformed since the previous Osaka Expo, an event alive with the hopes of post-World War II social reinvention. For Fujimoto, not all this change has been for the better. As such, his call for unity at Expo 2025 appears to be directed as much toward his compatriots as the world at large.

“Japanese society is getting rather conservative and not so open,” he said. “(It is) rather closed to other countries and cultures… So, I believe this is a wonderful occasion (to) reconnect Japanese culture to the world.”

CNN’s Hazel Pfeifer, Yumi Asada and Daniel Campisi contributed to this story.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2025 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.