How prevalent is the use of IVF, and what does the future of access to it look like?

PeopleImages.com – Yuri A // Shutterstock

How prevalent is the use of IVF, and what does the future of access to it look like?

At 34, Natalie, a doctor from Oregon, was struggling to build the family she longed for. At times, her sense of helplessness was overwhelming.

“All my friends had kids; they were all having their baby showers and their first birthdays. And you know, that stereotype about babies is everywhere. You couldn’t get away from it,” she told Stacker.

After trying to conceive for a year, Natalie turned to in vitro fertilization. However, her choices were limited since her insurance covered just three providers in her state—the only three in Oregon—and capped at $20,000. The cost of a single IVF cycle averages over $23,000, but most patients have to go through several cycles to conceive, spending closer to $50,000 for the entire procedure.

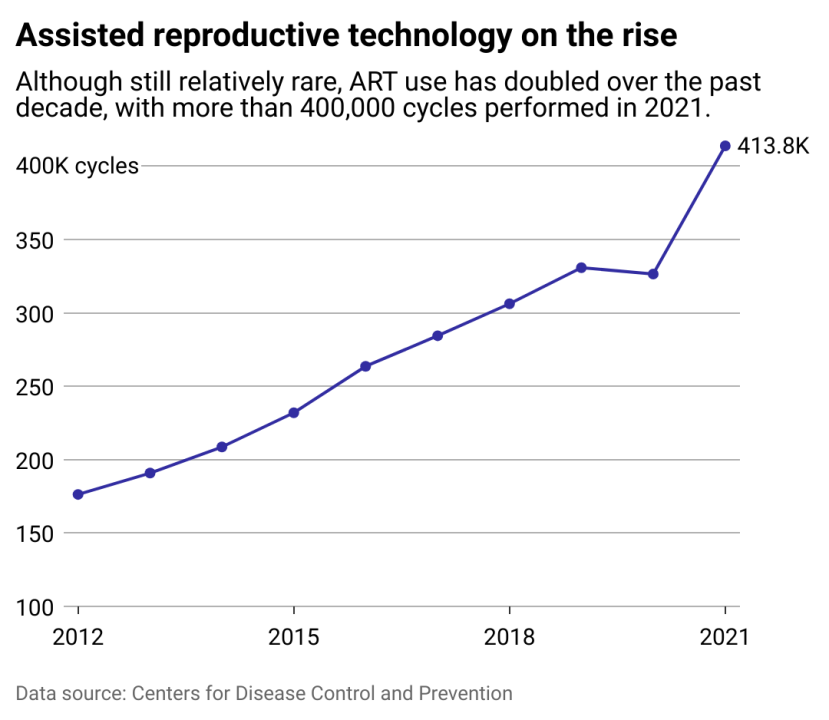

Natalie is one of the millions grappling with infertility in the U.S. who have turned to IVF to become parents. Over the past 10 years, assisted reproductive technologies like IVF have doubled, giving a boost to the country’s falling fertility rates. In 2022 alone, nearly 100,000 babies were born with the help of IVF. In 2018, the International Committee for Monitoring ART estimated that 8 million babies have been born as a result of IVF since 1978.

ART procedures were first developed over four decades ago, radically expanding possibilities for many families unable to conceive naturally. Incredible innovations in the field, increased awareness about infertility, and a rise of employers offering fertility benefits to their workforce—40% of U.S. organizations in 2022 alone—have helped to normalize infertility treatments.

But reproductive technologies still come with a high financial price, as well as an emotional and physical toll. Infertility treatments—and reproductive health care in general—still remain inaccessible to vast swaths of the population. Moreover, legal restrictions in some states have further curtailed the use of IVF despite the overwhelming public support for these procedures.

The 2022 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case allowed states to come up with their own anti-abortion laws. Moreover, several state legislatures have granted personhood status to fetuses, which could potentially extend to embryos, thus placing IVF in jeopardy.

With contradictory messaging from the current administration around reproductive technologies, the future of IVF remains murky. In April 2025, President Donald J. Trump eliminated the Center for Disease Control’s six-person team devoted to IVF research as part of massive layoffs.

The elimination of the Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance team, considered a vital asset in addressing infertility in the U.S., comes after Trump signed the Expanding Access to In Vitro Fertilization Executive Order in February. The impact of the directive, which calls for policy recommendations on expanding access to IVF treatment and reducing out-of-pocket costs, has yet to be seen.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to use data from the CDC and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology to examine the state of ART across the nation.

Editor’s note: Though “women” appears throughout this story, we acknowledge that not all pregnant people are or identify as women.

Anna Moneymaker // Getty Images

After the end of Roe v. Wade, calls to protect IVF gain traction

“Babies are little miracles,” Lindsey Pinkham, who paid out-of-pocket for IVF treatment in Orange County, California, told Stacker. After her first child was born, her second pregnancy was ectopic. Pinkham had surgery to end the nonviable pregnancy, and she said the damage to her fallopian tubes, her doctor told her, would affect her ability to conceive naturally again.

Pinkham, now 35, represents 1 in 6 impacted by infertility in the U.S. In 2021, 238,216 patients received ART treatments, averaging more than two IVF cycles each, according to the CDC’s 2021 Assisted Reproductive Technology: Fertility Clinic and National Summary Report. These treatments resulted in 189,034 live births, 112,088 clinical pregnancies, and 167,700 frozen eggs or embryos for potential future use.

Assisted reproductive technology refers to all fertility treatments that involve manual handling of eggs or embryos. This includes egg removal from a person’s ovaries, combining eggs with sperm in a laboratory to create an embryo, implanting the embryo in the patient’s body, or donating the eggs or embryos to another patient. The use of frozen eggs and embryos enhances the chance of pregnancy, but multiple cycles of retrieval, fertilization, and implantation are commonly needed. In most states, unused eggs or embryos can be donated or destroyed if the supply is no longer needed.

“I think going through a traumatic experience and loss really opens your eyes to the perspective that they are truly hard to come by for a lot of people—myself and a whole bunch of people I know—that needed the extra help,” Pinkham told Stacker. “It’s just a miracle that we have the technology to allow people to be able to create a family and be successful in that.”

In February 2024, IVF was thrust into the national spotlight when a ruling by the Alabama Supreme Court granted embryos the same constitutional rights as a person. The court’s “fetal personhood” decision “essentially gives frozen embryos in test tubes and freezers and fetuses the same legal rights as born children,” Melissa Goodman, Executive Director of the UCLA Center on Reproductive Health, Law and Policy, told Stacker. In other words, any embryo potentially damaged or destroyed during a procedure could make a patient and their doctor liable.

Several IVF clinics in Alabama suspended their activities after the ruling, but most have resumed in vitro fertilization services after the governor signed legislation to provide criminal immunity to patients and providers who “facilitate the in vitro process” or “transport of stored embryos.” The law does not address the question of personhood in embryos.

After the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, a third of states included fetal personhood into their criminal statutes—with at least 14 more introduced in the last year—which could be leveraged to directly target bans on IVF. Additionally, a guide by UCLA Law, last updated February 2025, shows that 28 states lack “shield laws” designed to protect people from out-of-state criminalization of reproductive health services.

Despite widespread disagreement with the ruling, including from the Medical Association of the State of Alabama, some legislators continue to push for IVF restrictions. Jason Thielman, Executive Director of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, urged the Senate to support government efforts to protect IVF access. He argued that 4 out of 5 evangelical Christians supported some form of IVF. Still, Republicans voted to block federal protections for IVF in June 2024, following a Supreme Court decision to protect the use of a widely used abortion medication, mifepristone.

“IVF is most certainly at risk,” says Goodman.

Stacker

The history of assisted reproductive technology

In 1978, the first baby was born with the assistance of IVF in England. Three years later, came the first IVF baby in the U.S.

When reproductive technology was new, a desire to further science, get recognition in academic journals and help people trying to conceive all drove the development of the field. “We were rewarded by being recognized as scientists. That seemed reward enough for most of the people,” Alan Trounson, a developer of key assisted reproductive technologies, told Nature in 2023.

IVF science evolved quickly. Because ART was initially classified as an in-office medical procedure rather than a drug or medical device, looser regulations both in the U.S. and abroad allowed for faster, cheaper testing and rollout to clinics without lengthy clinical trials. By the 1990s, the increase in patents for procedures boosted commercial gains in the field. Competition continued through the turn of the century as breakthroughs in stem cell science fostered new procedures, including embryo analysis and genetic testing. All the while, the number of IVF patients—and babies—steadily increased.

More recently, new discoveries in the field have been driven by commercial incentives to secure patents. There are now hundreds of IVF patents submitted every year and stricter regulations around ART in some countries. With increased commercialization, treatments might be more expensive and less accessible going forward.

In the past decade, in vitro maturation technology was introduced, enabling eggs to mature outside the body before implantation, a process benefiting patients with preexisting conditions like cancer. Researchers are currently developing translating in vitro gametogenesis technology into humans. The treatment, once considered the stuff of science fiction, aims to take blood or skin cells to create egg or sperm cells. The technique is projected to work regardless of the sex of the donor, multiplying the opportunities for creating embryos and supporting same-sex family planning.

Meanwhile, along with advances in technology, costs have steadily increased. IVF costs around $50,000 per patient on average in the U.S., which mostly covers the cost of drugs. Despite the exorbitant costs, more than 4 in 10 adults say they have used fertility treatments or know someone who has, according to a 2023 Pew Research survey. Moreover, despite greater restrictions, the IVF market in the U.S. is estimated to triple between 2017 and 2025.

Stacker

Access to IVF varies by geography, race, income

Like many people struggling with infertility, Natalie considers herself lucky to have had access to IVF at all. “When we did the first round, I got pregnant for the first time, and I was just over the moon. And then when I lost it, that was just the most pitting thing in the whole world, having gone through all of that. All of those hormones. All of that money. All of that time.”

After she miscarried, Natalie was grateful that Oregon’s laws gave her access to medicines that would safely allow her body to pass any pregnancy tissue. “If I lived in Texas, I would have had to just sit and wait and hope that I wouldn’t get sepsis from this dead embryo inside of me,” she says.

After three rounds of embryo transfers and two-and-a-half years after beginning IVF, Natalie finally gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

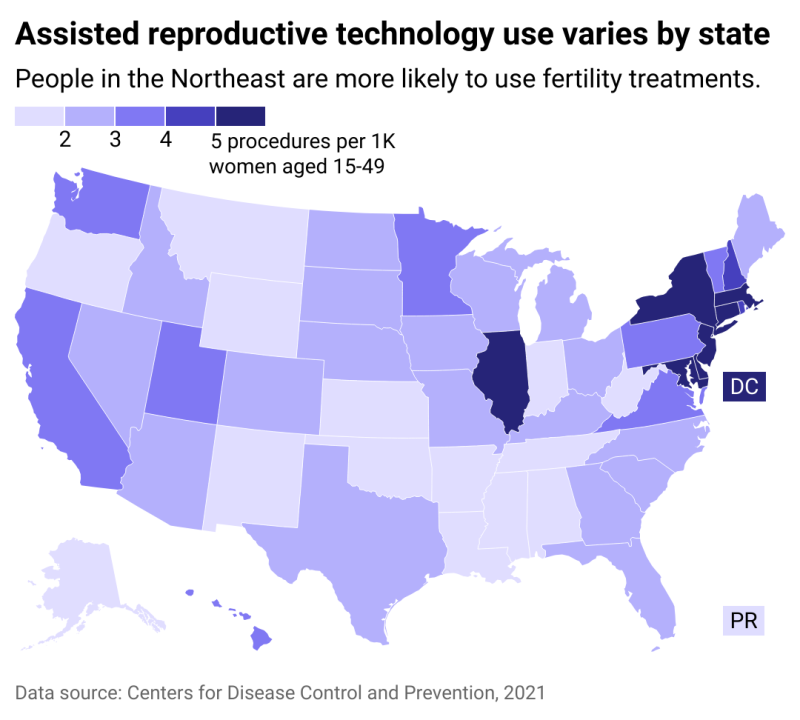

Not everyone is so lucky, however. Income, race, and sexual orientation also factor into the probability of having a child through IVF. According to Fertility IQ, patients are twice as likely to have successful IVF pregnancies if they have a household income of at least $100,000. Data from the Centers for Disease Control also shows that more fertility treatments occur in the Northeast, where the highest levels of wealth are concentrated. Compared to white women, fewer Black and Hispanic women report having utilized medical services to get pregnant.

Among states and insurance companies that offer fertility treatment coverage, most require a clinical diagnosis of infertility, which is commonly defined as six months or more of unprotected sex. However, requiring a demonstration of infertility excludes many people from LGBTQ+ communities or single people from qualifying for benefits. Some state mandates, in Maryland, Arkansas, and Hawai’i, even necessitate that the person seeking IVF insurance coverage uses their spouse’s sperm.

Despite gains in coverage, many available health insurance plans do not include fertility benefits, according to Contemporary OB/GYN. Only 11 states mandate comprehensive IVF and infertility insurance coverage, mainly on the East and West coasts—although Goodman says she has noticed an increasing trend for more coverage, according to data from RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association. Even when insurance does offer infertility treatments such as egg retrieval, egg freezing, and fertilization, challenges and out-of-pocket costs remain for many families.

The current political climate is creating anxiety for future parents and people who have genetic material stored. For Natalie, who is now medically unable to carry another child, but still has two frozen embryos left in storage, a shifting IVF landscape may present additional challenges.

“The fear of what will happen to those embryos is real,” she said.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Sofía Jarrín.

This story was produced by

Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with

Stacker.

![]()