How transportation investment could improve pedestrian safety in Black communities

Ryan DeBerardinis // Shutterstock

How transportation investment could improve pedestrian safety in Black communities

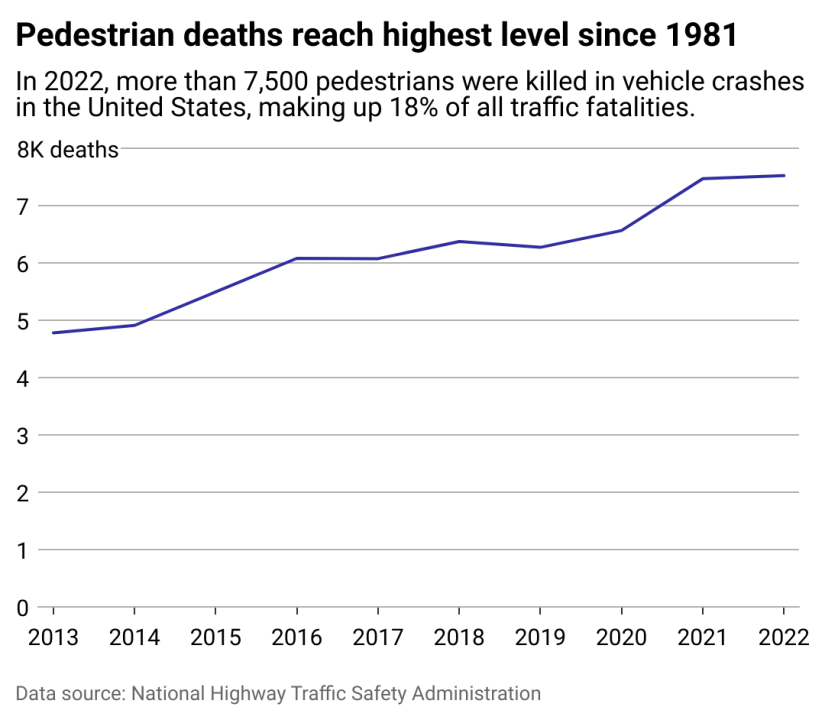

Walking down American roads is more dangerous than it’s been in decades. In 2022, traffic crashes killed 7,522 pedestrians, hitting its highest death count since 1981, according to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. That year, an average of 21 people traveling on foot were killed each day by a moving vehicle.

Pedestrian deaths have been on the rise over the past decade, at least partially due to the increasing popularity of SUVs, as larger vehicle models create more prominent blind spots for drivers. Because they are more likely to strike passengers in the head, pedestrian crashes involving vehicles with a higher hood are more likely to be deadly, according to a 2023 study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Despite this risk, larger vehicles like SUVs and pickup trucks have grown more popular with American drivers, representing 75% of all new cars sold in 2024, according to JATO Dynamics data.

While pedestrian traffic crashes have become more deadly, not all walkers feel the impact equally. These crashes often disproportionately affect vulnerable communities, including older adults, people with disabilities, and people walking in lower-income areas, many of whom are less likely to rely on cars to get around.

Racial disparities among pedestrian victims of deadly crashes are also noteworthy. Compared to white Americans, Black Americans were killed in traffic-related crashes more than twice as often while walking in 2017, according to a 2022 Harvard and Boston University study. In 2024, a report by Smart Growth America found that emergency room visits for injuries while walking for Black people happened at nearly double the rate of non-Hispanic white people in 2022.

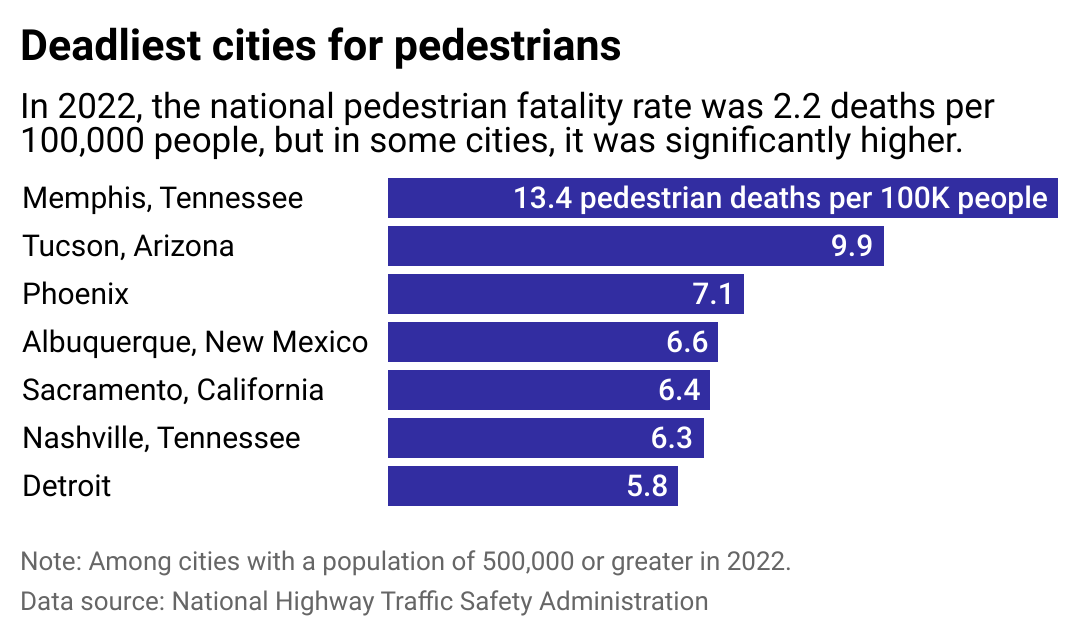

To understand why U.S. streets are becoming deadlier for those traveling on foot, National Health Ratings examined NHTSA data to find which cities have the highest rates of pedestrian deaths, break down why traffic crashes disproportionately kill Black pedestrians, and explore what some cities are doing to boost pedestrian safety.

National Health Ratings

Pedestrian deaths on the rise

Most pedestrian fatalities occur in urban areas, apart from intersections, and typically at night when it’s harder to see people walking along the road. A 2023 study in the Journal of Transport and Land Use found that pedestrian fatality hot spots often shared common characteristics, like multilane roadways with five or more lanes to cross, 30 mph or higher speed limits, and traffic volumes surpassing 25,000 vehicles daily.

Dangerous road infrastructure is one of the most significant contributors to pedestrian deaths across America, and many cities are grappling with how structural racism has shaped street designs in disinvested neighborhoods.

The highway boom of the 1950s and 1960s saw many interstates routed through Black neighborhoods, which often deliberately destroyed or isolated these communities. A 2017 Department of Transportation report determined the U.S. interstate system displaced over a million people and businesses in less than two decades.

In North Nashville, Tennessee, for example, the construction of Interstate 40 and I-65 split its Black communities into three and nearly destroyed its then-thriving Jefferson Street corridor. In 1967, Black residents protested the construction, even suing the state in federal court. However, Tennessee highway planners forged ahead with the plan, which displaced nearly 80% of Nashville’s Black businesses and over 1,000 residents. But it also became difficult to safely walk between the two neighborhoods, which were now divided by highways and converging traffic.

Dividing Black communities with highways resulted in higher volumes of traffic running through them, creating more dangerous, less walkable neighborhoods that continue today. A 2023 UNC Chapel Hill study found that neighborhoods that the federal government redlined—a now-illegal policy that encouraged banks to deny mortgages to Black households and segregate them from white households—also became targets for building new arterial roads and highways, leading to higher rates of pedestrian traffic deaths decades later. It’s a cycle that’s hard to break, leaving many roads deadly by design.

National Health Ratings

Major cities work to reduce pedestrian deaths

The six deadliest places for pedestrians in 2022 were fast-growing, auto-dependent metro areas in the Sun Belt, where the population is increasing faster than other parts of the country, and where streets center around the automobile.

Southern cities that lack suitable public transit options frequently have the highest fatality rates for pedestrians, according to the nonprofit, The Eno Center for Transportation. With fewer transportation options and rising inequality, residents who cannot afford to drive a car end up walking through high-traffic roads, often without sidewalks or lighting fixtures to illuminate pedestrians after dark. Low-income populations are also growing faster in these auto cities, living in neighborhoods that are inconveniently far from jobs and challenging to serve with public transit, according to a 2020 report by Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research.

High traffic speeds are also a great contributor to pedestrian deaths, with pedestrians being five times more likely to die in a crash if the car is going 40 mph than if it is going 20 mph. Phoenix, Detroit, and Memphis, Tennessee—all among the deadliest metros for pedestrians—saw some of the highest average speeds among 30 top metro areas, according to a 2023 analysis from Streetlight Data.

Memphis saw the highest pedestrian death rate among American cities in 2022. Much like Nashville, the interstates running through Memphis—another highly redlined, majority-Black city—have left streets deadlier for people traveling without a car. This is especially the case on arterial roads, where 85% of pedestrian traffic crashes happen, according to a 2025 AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety case study.

How cities are making streets safer for pedestrians

Since climbing to the top of pedestrian fatalities, Memphis city officials have enacted changes in recent years, including educating drivers, upgrading streetlights, and installing bright, colorful crosswalks so pedestrians can be more visible to drivers at night. While some of these solutions might be a step in the right direction, pedestrian fatalities are largely a result of the structures and policies that make walking unsafe—a devastating outcome of developing roads designed to primarily serve drivers.

The cities with the most pedestrian deaths could look to solutions adopted by metros like New York City, Boston, and Chicago, which have some of the lowest pedestrian fatality rates in the country. These cities, among others, share similar approaches to stopping pedestrian deaths through programs often dubbed “Vision Zero.” First emerging in Sweden in the 1990s, Vision Zero approaches to safety materialized from the belief that even one traffic fatality is too many, creating policies meant to eliminate all traffic fatalities and serious injuries.

In 2014, New York City launched its Vision Zero program, which lowered speed limits to 25 mph and increased traffic enforcement through 24-hour speed cameras that automatically ticket vehicles traveling above the limit. Over the last decade, these initiatives have helped reduce pedestrian deaths by 45% and saved the city more than $90 million in Medicaid expenses in the program’s first five years. The city’s Black and low-income residents, in particular, have experienced a reduction in traffic-related injuries as a result of Vision Zero, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2024.

Meanwhile, Boston’s Vision Zero reforms also included lowering its speed limit and embarking on projects to slow down busy streets, including reducing lanes on high-traffic roadways and raising speed bumps and crosswalks. And in Chicago, many of the city’s Vision Zero policies have involved altering the designs of streets themselves, such as adding traffic-calming features like bump-outs, which slow cars down as they turn, and making pedestrian refuge spaces in the middle of streets.

For many cities nationwide, changing how streets work has become the key to stopping pedestrian traffic deaths and reducing harm to the most vulnerable road users.

Story editing by Tim Bruns. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story was produced by

The Data Project and was produced and

distributed in partnership with

Stacker.

![]()